Rampart Road : The Whole Story

Rita L. Jacob

The foundations of Rampart Road were laid along the line of the old city ditches; ending near the top of Winchester Street where one of the city gates once stood. The work started in 1895 and, by the following year, was sufficiently complete to feature on a new city map. The Invicta Leather Works, which towered over some gardens, was not part of the original development but moved to Paynes Hill in 1902 following a fire at it’s premises in Endless Street.

The Houses

The terrace houses in Rampart Road, described by Geraldine Symons in Children in the Close as ‘drab villas’ were, in fact, an eclectic mix; varying in size, style and level. Most of those on the east side can still be seen today; the exception being a block of three-story properties now replaced by more modern dwellings. Each of these had an entrance on the first floor accessed by a flight of steps; the ground floor below forming a basement. At the beginning of the century, one was believed to be haunted; Geraldine Symons writing :-

‘One of the basement houses on the right was haunted. (What by we didn’t know.) That’s why it was empty. No one would live there. We could only guess at the horrifying happenings that the blank, dirty windows had once concealed, at what they might be hiding now. Lifting one’s eyes, one looked with a crawling spine for a dim white face, imagined a cobwebbed wedding cake and an old Dickensian bride.’

If this was a reference to the house opposite Numbers 16 and 18, a tendency to flood may have been a more rational explanation; later occupants often having to ‘bale out’ the ground floor whenever there was heavy rain!

The houses on the demolished west side were on a lower level than those on the east; several having front doors more than thirty centimetres below the road. They also had smaller amounts of land at the front, a number at the Milford Street end having nothing more than a stone step separating them from the pavement. The height of the rear gardens, however, varied dramatically; those of Numbers 10 to 20 being just below the back bedroom windows and reached by climbing eight steep brick steps at the end of the concrete yard.

As on the east side, the largest properties were at the St. Ann Street end; those with land at the front having bay windows on the ground floor. All had hallways leading to sitting rooms, dining rooms and stairs; unlike the houses opposite Percy Churchfield’s Dairy where front doors opened straight into the main living space with only a scullery beyond. Few on either side had bathrooms before the 1960s; it being necessary to sacrifice a coal house or back bedroom in order to build one. Nevertheless, dwellings without indoor facilities had a toilet in close proximity to the back door instead of in a shared block some distance away; this being a norm in much poorer areas.

The People

In his book I Remember Arthur Maidment alludes to the poverty and community spirit that existed in the area at the beginning of the twentieth century; his own home being one street away, in Culver Street :-

‘Generally speaking there was a shortage of money, holidays were almost unknown, but the street had a community spirit seldom found today.’

During the First World War, fear of air raids, the introduction of a blackout and severe food shortages made life even more difficult; particularly in the winter of 1917/1918 :-

‘When food was dreadfully short, a communal Soup Kitchen was set up in the Lear Memorial Rooms in Gigant Street. We went along with basins and were served from a tap which was at the end of a pipe coming through the wall into the street where trestle tables had been erected.’

Also, men returning from military service often found themselves without regular employment, a situation repeated in the 1930s when, each day, the queue of jobless stretched from the Labour Exchange at the end of Catherine Street to the Milford Street corner.

The area also had it’s share of casualties at least eight of the men killed having links with Rampart Road; Frederick Massey, Sidney Massey and Charles Munday living at Number 38. Three Massey brothers and Sydney Pitman from Number 39 all served in the Wiltshire Regiment and were ex-members of St. Martin’s Church Lads Brigade; perhaps joining up in a ‘pals’ initiative since Lyn Macdonald often mentions a Church Lads Brigade in her history of the Somme.

The first Salisbury Directory published after First World War shows that, in 1922, the Rampart Road population was as diverse as the housing; ranging from gardeners, labourers and boot makers to clerks, teachers and a beadle! By the end of the Second World War, this social gap had almost closed, most occupants working in skilled trades or the public services. Yet, as late as 1969, few owned the houses they lived in; the majority renting from private landlords who usually owned several properties in the road.

Generally, the families who lived in Rampart Road in 1945 were not those living there in 1922; the population more or less changing completely within a period of twenty three years. Conversely, from 1945 to 1969, there was little movement; the community becoming relatively static and close knit. Everyone knew everybody else who lived on their side of the road as well as most of those living opposite; children feeling safe enough to knock on any door when in trouble. The families living beyond Milford Street, however, remained comparative strangers unless they had relatives living in the lower part; probably feeling more affinity with neighbours in Winchester Terrace than those who merely shared their postal address.

The Gates was one family listed in the 1922 directory who were still living in Rampart Road, at Number 6, during the 1950s. In February 1931, Mr and Mrs Gates who already had six daughters, became local celebrities when Pamela, Peggy and Patricia were the first triplets to be born at Salisbury Infirmary. The triplets who were later followed by Ronald, the only son, went to Saint Martin’s and Saint Edmund’s schools before working in Boots and marrying husbands who had done their National Service in Wiltshire. On 17 February 2011, although no longer living in Salisbury, they once again featured in the local paper having just celebrated their eightieth birthdays.

Although some bombs fell during the Second World War, Salisbury escaped the destruction wrought on other cathedral cities; it being a local belief that the spire was an important navigational point for German pilots. Nor did the area experience the dire food shortages of the First World War or the terrible casualties; many of the men living in Rampart Road being the wrong age for conscription or in reserved occupations. Some families, however, took in evacuees from Portsmouth while others were billeted in Beckingsdale House opposite Lannings.

On VE day, Rampart Road was decked in flags; Number 16 also displaying a large V and E made of wood and light bulbs. Eight years later, the same flags were brought out to celebrate the coronation; the VE being replaced by an illuminated picture of Queen Elizabeth. Unfortunately, however, the residents could not hold a street party in Rampart Road itself; some events taking place in St. Martin’s Church Street with the tea being eaten in the gardens of the Tollgate Inn. Sadly, by the time Salisbury celebrated the Silver Jubilee in 1977, the west side of Rampart Road was no more and families choosing not to relocate to the Tollgate Road flats scattered all over the city.

Shops and Businesses

Before the ring road was built, Rampart Road ended at Milford Street on the west side and Hill View Road on the east; the block of houses across the top of Winchester Street then being Winchester Terrace. The pub at the end of the latter, now the Winchester Gate, had a London Road address and the name, The London Road Inn; Peter Daniel’s book Salisbury containing a photograph of it taken in1903.

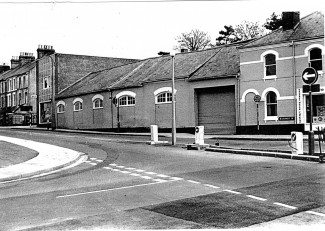

The site at the opposite end, on the corner with Tollgate Road was occupied by very different businesses during it‘s history; at the beginning of the century being the St. Ann’s Ironworks and later, the New Forest Laundry and a garage. The works, usually known as Armitages, were owned by John Varley Armitage and, in the 1920s, employed a moulder, two fitters, a blacksmith, a labourer and three apprentices in addition to John’s three sons. Then, castings of up to five hundredweight, including drain covers, were made on the premises; repairs to traction engines being an Armitage speciality.

The newsagents on the St. Ann’s Street corner was also a family business; belonging to the Lannings until it’s demolition in 1965. The last proprietor was Miss Flora Lanning; a diminutive lady usually dressed in a patterned smock, dark skirt and thick lisle stockings. Throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s, newspapers and magazines were arrayed on the counter with chews, lollipops, sherbet dabs and barley sugar sticks on a glass shelf above. The sweets sold by the quarter were kept in jars on the wooden shelves behind; amounts required being carefully weighed out and put into paper bags. The shop, however, always reeked of paraffin; this being one of the commodities that Miss Lanning sold in addition to fire lighters and kindling. Also, the shop was so cold during the winter months a tall black stove was kept burning; the flames whooshing up every time there was a draught!

Number 62, at the top of Rampart Road, was once the Clovelly School of Music which had moved up from number 3. By1922, however, the premises had become St. Ann’s Dairy; a directory describing Mr Percy as a dairyman and his wife, the proprietoress. This shop, re-named Percy Churchfield’s, was managed by the Baines family in the 1950s; selling cooked meats and general groceries as well as milk, butter and cheese. The adjoining house was also part of the business and the home of the Percys and Baines during the periods they were responsible for shop. This was something of a disadvantage as residents, running out of milk, would knock on this door when the shop was closed; particularly on Sunday mornings when custards, junkets and blancmanges were being prepared for afternoon teas!

Traffic and Cows

Rampart Road linked routes to London, Southampton and the Dorset coast yet, at the beginning of the century, children were able to play games such as Birds, Butterflies and Beasts across it; most vehicles then being horse-drawn. Also, even during the First World War, a very young Arthur Maidment was allowed to make to his own way between St. Martin’s Infant School and St. Martin’s Men’s Club where his mother was attending a Mothers Union meeting; even Friary Lane being dangerous forty years later when various Council depots were located in Bugmore.

By 1935, however, the increase in motor traffic necessitated the installation of traffic lights along the London Road to ease the flow and improve safety. This action may have had the desired effect for a few years but, during the 1950s and 1960s, there were often long queues and gridlocks; residents wishing to cross Rampart Road having to squeeze or climb over the bumpers of stationary cars. Moreover, vehicles sometimes jumped the lights; a fatal accident occurring in June 1940 when a car did so and collided with a bus crossing the junction from Milford Hill.

During the Second World War, convoys of military vehicles rumbled along the road; causing the bay windows of some properties to subside. Also, after one of the Levers’ sons had a fatal encounter with an American army lorry, parental attitudes to playing outside began to change; the children of subsequent decades being confined to their gardens or designated play areas such as the Greencroft and Riverside Gardens. Similarly, until the Council provided a crossing patrol at the bottom of Rampart Road, young children were either escorted all the way to school or crossed over the most dangerous roads; this happening four times a day if they came home to dinner.

Cars, lorries and the Number 37 bus from Southampton were not the only hazards faced by residents wishing to cross Rampart Road; it being the practice to drive cattle along the roads between Milford Goods Station and the market. With the cow walloper following behind, the animals could break from a trot into a full gallop; it also not being unusual for one to stray into a front garden and peer through the window! According to Arthur Maidment‘s biography I Remember, such droving diminished during the 1930s; motor vehicles being able to transport cattle from door-to-door. Yet, Percy (Porky) Andrews, dressed in a long brown coat and flapping gum boots, could still be seen swinging a cane and hollering well into the 1950s!

Final Days

Change began in the late fifties and early sixties with the construction of Salisbury Technical College and the demolition of houses in the Friary; many of which were sub-standard and beyond modernisation. The latter was not true of properties in Rampart Road; renovated houses on the east side now selling for over £200,000.

The plans for Churchill Way initially caused a lot of uncertainty; residents not being sure which properties were scheduled for demolition or loss of land. Those who owned their own homes were in a particularly invidious position; knowing that any money they received under a Compulsory Purchase Order would be insufficient to buy a similar property – or one at all! Therefore, once the bulldozers began to roll in, owners and tenants found themselves forced into Council accommodation with a minimal amount of compensation; social housing still carrying a stigma in the 1960s.

Rampart Road became a rather unpleasant place during the last few years; houses being boarded up as they were vacated and demolition work already taking place in St. Ann Street. In addition, Number 14 became the scene of a violent murder when an obsessively jealous husband stabbed his wife and then telephoned the police to report the deed. This family had recently moved from outside the area; choosing the empty property almost on a random whim. Those who were being re-homed in the new Tollgate Road flats were some of the last to leave; the Council at least making an attempt to keep part of the community together!

People may have been less bitter about losing their homes if they thought the new road would fulfil it’s purpose; the site being controversial even in the sixties. On the other hand, one of the reasons Rampart Road is remembered with affection is that it was destroyed before radical change took place although the latter was gradually creeping in. For, by 1969, some of the elderly residents had either died or moved nearer their children while the younger couples, if they could afford to do so, had sought properties they could actually own. This change in population would have accelerated once landlords began disposing of houses, new tenants likely having no roots in the area and regarding the latter as mere steps on the property ladder!

Comments about this page

First visiting Salisbury in 1969 but later coming here to live in 1974, living on Milford Hill about 8 or 9 houses up for 18 months . Then moving to Bemerton Heath in 1976 I found this story very interesting and it confirmed my thoughts about what terrible destruction had been wrought on Salisbury and the people who inhabited it.

There is no excuse whatsoever at all to ruin a city and more importantly to take people’s homes from them. The amount of depression caused to many of these residents whose homes were destroyed was terrible. Something no one, except a few, really knows about. Hang your head in shame those of you who thought this was a good idea. The arrogance and lack of empathy is and was astounding. Just look at Salisbury now and how Churchill Way has destroyed the city. Churchfields industrial estate planned so that giant, articulated lorries have to turn under the railway bridge through residential areas – what a stupid idea.

If anyone really thinks we have gained anything (apart from front windows looking at a concrete wall) by building the flyover alongside Rampart Road maybe they lack vision or at the very least aesthetic appreciation. Old houses could have easily been renovated easily if the will was there but planners just wanted to make their mark and start afresh – shame on them.

Add a comment about this page