The First World War

Rita L. Jacob

The information relating to the First World War is not always specific to the Milford Bridge area or even to Salisbury; measures such as the introduction of a blackout in 1917 affecting the whole population. At the other end of the spectrum, there is that pertaining to a particular house or family; the fact that three casualties came from 38 Rampart Road being an example.

Recruitment

As soon as war was declared on 4 August, there was a rush to join the army; one of the new recruits being Herbert Bundy who had given up the tenancy of The London Road Inn in order to enlist. A photograph taken in September 1914 shows him standing in a group about to board a train; this including plasterers, plumbers and postmen. Some of these ‘brave lads’ would never come home; perhaps joining the thousands with ‘no known grave’ except the place where they fell.

Another First World War photograph shows Minster Street and the Cheese Market decorated with bunting and banners; the London City and Midland Bank acting as a recruiting office. Many of those who passed through these doors and those of other local recruiting offices enlisted in the Wiltshire Regiment; the Masseys of Rampart Road having four sons serving in the 1st, 2nd and 4th battalions. Some, however, were underage when enlisting or too young to serve abroad; William Fry, who lived in Paynes Hill, being only seventeen when he was killed in August 1915 at Gallipoli.

Three of the Massey brothers and Sidney Pitman had been members of St. Martin’s Church Lads Brigade. They all enlisted in the local regiment but, by September 1914, the Church Lads had their own brigade formed on an estate near Denham by the local squire, Major Wyld. Detachments of ‘Lads’ arrived from all over Great Britain to join the brigade; the latter later becoming the 16th Battalion Kings Royal Rifles Corps often mentioned by Lyn Macdonald in her book on the Somme offensive. As Richard Broadhead only lists those killed in Salisbury Soldiers, it is not known whether any of St. Martin’s Church Lads joined this brigade; this taking some recruits rejected by the army elsewhere.

The Arrival of Colonial Troops

Within seven weeks of war being declared, Canada had assembled an Expeditionary Force of over 30,000 men at Valcartier, about sixteen miles to the west of Quebec City. This force was transported to Britain where they spent four dismal months on a cold, wet Salisbury Plain along; troops from other parts of the empire also being encamped around the city. At some point during the war, some were billeted with local families; this having a romantic outcome in the case of the Tryhorn family who welcomed two into their St. Edmund‘s Street home. The eldest daughter, Violet, married the Australian soldier and went to live with him on a sheep farm in Queensland, while her younger sister, Dorothy, became the wife of John Homersham Evans, a Canadian immigrant born in London. The latter did not return home to his adopted country when the war ended but settled with Dorothy in Ivy Place; working at Southern Command during the Second World War after several moves and jobs.

The Civilian Populaion

Towards the end of the war, fear of air raids, the introduction of a blackout and food shortages made life difficult; the latter becoming so severe during the winter of 1917/1918. that a communal Soup Kitchen was set up in the Lear Memorial Rooms. Those who used it brought their own bowls and basins which were filled from a tap connected to a pipe in the wall; this taking place outside in Gigant Street where trestle tables had been erected.

Despite their own hardship, people still did what they could to help those who were even worse off. Members of the Salisbury Division Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment, including Arthur Maidment’s father, met ambulance trains and ferried the wounded to various military hospitals around the city while Queen Mary’s Needlework Guild produced a continuous supply of garments and equipment to these as well as parcels for our fighters. Also, when air raids began, various items were collected for fleeing Londoners; these, including Arthur’s wicker pram, being stored in the premises once occupied by the Rainbow Laundry.

Between 1914 and 1918, Invicta Workers produced leather for thousands of army boots while Arthur Maidment’s father made field kitchens for the Canadian army; probably at Farrs the coach-builders in Brown Street. Sources, however, have little about female employment during the period; other than voluntary work, nursing and the Women‘s Land Army which had schools at Longford Castle and Wilton House. Nevertheless, as in other parts of the country, it is likely that women took over some jobs previously done by men; young Rose Gardner of Greencroft Street becoming a telegraph girl.

Casualties

The casualty figures for the First World War are so huge that they are beyond comprehension; the scale and impact only being realised when viewed at a local level. For, during the conflict, Salisbury lost four hundred and fifty nine of its young men; train loads of sick and wounded also passing through the city on their way to the various military hospitals set up around it.

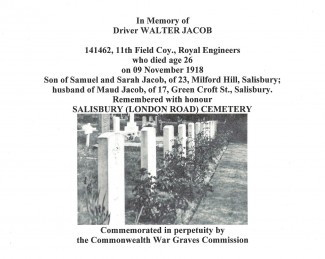

In Salisbury Soldiers, forty three of the casualties have links to addresses in the Milford Bridge area; this rising to fifty four if those in St. Martin’s Church Street, St. Ann’s Street and St. Edmund’s Church are included. Culver Street, Gigant Street, Trinity Street, Milford Street, Milford Hill and Rampart Road all had multiple casualties; some families like the Masseys, the Burbages, the Sainsburys and the Amors losing more than one son. L/Cpl George Green of Winchester Street was killed in Belgium just twenty days after war was declared while Driver Walter Jacob of Greencroft Street was the last Salisbury man known to have died before Armistice Day; succumbing to pneumonia in a military hospital on 9 November 1918.

Geraldine Symons in her book Children in the Close mentions a basement house in Rampart Road believed to be haunted. Arthur Maidment also writes about this property in I Remember; this standing ‘some sixty yards‘ from Armitage’s closed down ironworks and remaining empty for about fifteen years.Arthur, however, goes on to give a more rational explanation; the owner living alone and being killed during the First World without leaving an apparent heir. Yet, the tenant is not one of those listed in Salisbury Soldiers unless his address is one of the number simply given as St. Martins; the mystery continuing!

The Aftermath

When the Armistice was announced in front of the Guildhall, the mayor felt he could say little more than ‘thank God the war is over’. Unfortunately, this declaration was followed by an outbreak of influenza; Arthur Maidment observing ‘More died from this scourge than were killed in the war’. Perhaps for this reason, peace celebrations were not held until the following July; children from Salisbury’s infant schools having a Peace Tea in Dr. Bourne’s field and older children taking part in a pageant of Salisbury’s history two days later. Finally, in February 1922, Tom Adlam, who had received a Victoria Cross for bravery during the Battle of the Somme, unveiled the city’s war memorial in the Guildhall Square.

For thousands of families, however, the suffering did not end on 11 November 1918; sometimes being perpetuated through several generations. Having been a prisoner of war, Phyllis Maple’s father was malnourished and unable to find work for two years while John Evan’s family was affected by his unpredictable behaviour after being severely wounded. Walter Jacob’s children, however, were bereavement victims, his widow, Maud, becoming ill and dependent on them after the death of her Wally. As a result, her son, Kenneth, did not marry until after her death in the 1940s, his sister remaining single and lodging with the couple in what had been her family home.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page